In Pakistan in 2003, Fatema was 11 when her mother told her they were going to a place that would relieve the stomach pain the preteen was having. She was in for a cruel surprise.

Going to this mystery place was Fatema and three other women: Fatema’s mother, aunt and slightly older cousin. They arrived at what seemed to be an ordinary house in Pakistan. Not a clinic or hospital, but a house Fatema recalls. Once inside two women guided Fatema’s aunt and cousin into another room and closed the door behind them. The two women didn’t look like doctors or nurses, they were dressed in the traditional tunic and loose pants. Fatema was confused, but didn’t think to question anything at that age. She trusted her mother. While Fatema and her mother waited, she remembers hearing her cousin scream out in pain. Five minutes later, her aunt and cousin finally emerged from the room. Fatema’s cousin looked pained but remained silent before she laid down on a mat in the living room and quietly fell asleep. Then it was Fatema’s turn. Her mother led her into the room with the two women.

They told me to lie down. Then one woman spread my legs, took off my underwear as my mother held down my arms. I saw one woman was cleaning a blade … and I screamed. says, Fatema, now 25.

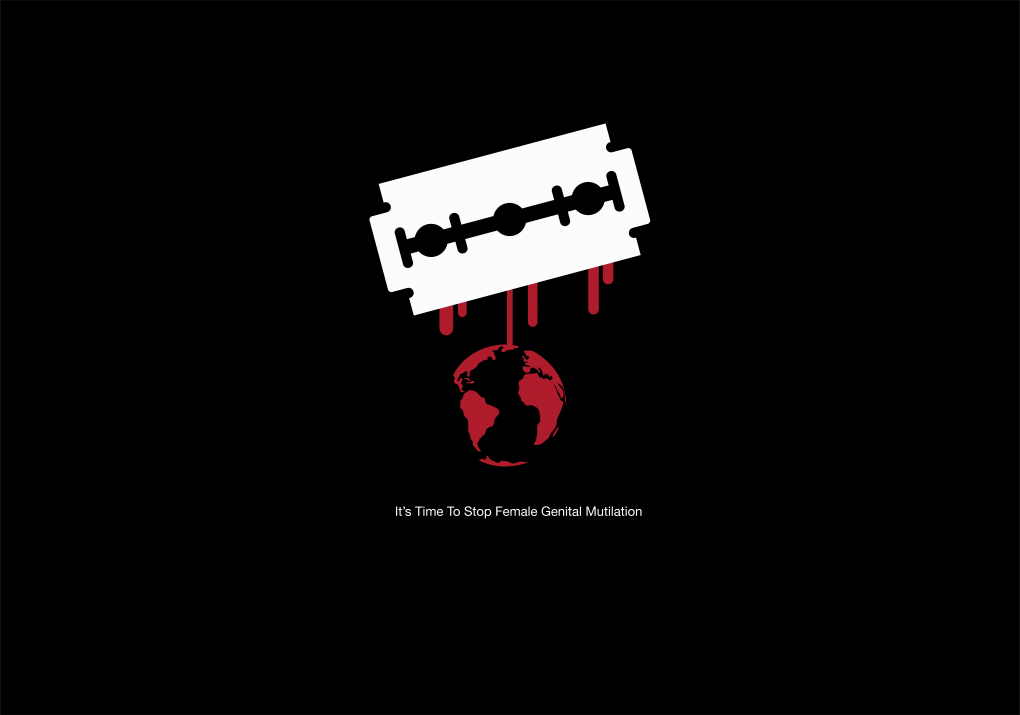

It took no more than a minute to cut part of Fatema’s clitoris and deprive her a lifetime of pleasure, a ritualistic procedure known as female genital mutilation or FGM. That’s the point of FGM. The practice, which is declared a crime in some 40 countries, including the US, is meant to take away all sexual urges from girls and women. Worse, it’s estimated that about 200 million women globally have been subjected to one of four types of FGM, which ranges from cutting the outer layer of the clitoris to the removal of the entire labia.

The World Health Organization bluntly states that FGM has no known health benefits, and only harms. Girls and women have died from excessive bleeding and infections from FGM, which is internationally recognized as a human rights violation. According to the United Nations, the rate of FGM has declined in the last three decades but some countries have been slower than others to stop the practice, such as Mali in Africa.

Fatema has been monitoring online coverage of the landmark case in Detroit, MI where eight Indian-American doctors and parents are accused of secretly mutilating girls in a clinic, the first charges of FGM since the US officially banned it in 1996. One of the accussed, Dr. Jumana Nagarwala, was arrested in April but later released in September on a $4.5 million bail as she awaits trial. The parents who took their girls to the clinic have also been arrested. Each of the accused are claiming “religious freedom” and that the procedure performed wasn’t mutilation but “cutting.” Their defense lawyer has even compared it to male circumcision, a common and acceptable practice in the US with religious ties.

Fatema, who belongs to the Muslim community of Dawoodi Bohras, the same that the Michigan doctors and their clients belong to, believes the entire practice should be a crime regardless of how deep the genitals are cut. “It affects our sex life after marriage. Both my sister and I can’t climax. This is FGM, it doesn’t matter what level. The whole thing is wrong.” says Fatema while in a crowded food court at a mall in Istanbul.

Fatema, a university student in Istanbul, Turkey, is sharing her story publicly, but anonymously, for the first time. She speaks in English expressing emotional words with stoic calm. Her deep brown eyes focus on recalling the physical trauma that won’t heal. FGM is irreversible. If she reveals her real name, her family and community may ostracize her, she says. But if she remains silent, girls among Dawoodi Bohras, a Shia sect of Islam with about 1.5 million followers, will continue to be mutilated.

I feel like throwing up when I think about [the incident]. Even now my heart beats fast. It made me feel disgusted, Fatema says.

In Pakistan, the law doesn’t explicitly forbid FGM. Many Pakistanis don’t even know that it exists in their country, but Pakistani activists say FGM is practiced in several communities, especially among the Dawoodi Bohras and Sheedi Muslims who nip the clitoris. Fatema is a practicing Muslim and proud member of Pakistan’s 100,000 Dawoodi Bohra community. Dawoodi Bohras are spread across the globe but the majority live in India and follow a dai, a living spiritual leader, who guides them in their traditions.

Saima Baig, an environmental consultant and Karachi-based blogger, who wrote about FGM in Pakistan, says an explicit law prohibiting female genital mutilation and implementation of that law is a necessity. “A few years ago people did not even know that this was practiced in Pakistan. Now with social media campaigns and blogs, more people know about it. The government needs to recognize this as anti human rights and implement laws that punish those who practice it.” Baig says in an email to Rights Universal. But Fatema says many families in her Bohra community don’t abide by national laws. Their traditions come first.

Mufaddal Saifuddin, the current Bohra leader, or dai, advises parents to cut their girls before they reach puberty as part of what they believe is Islamic tradition. FGM isn’t mentioned in the Quran, Islam’s holy book, but many Muslim communities see it as part of their identity. “Unless the Bohra chief, known as dai, issues a decree to forbid the act, the practice will remain firmly rooted in the people’s culture and will continue to be practiced,” says Qamar Naseem, program coordinator for Blue Veins, an Islamabad-based non-governmental organization lobbying against gender violence.

Fatema says the Bohras in Pakistan believe in educating women and giving them the right to work. They are generally apolitical, entrepreneurs who are tight-knit, and their lifestyle revolves around charity and being there for their community members. But the darker side is the immense pressure to marry within the faith and to follow outdated traditions like FGM, she says.

Fatema didn’t understand what had been taken from her at age 11. When she came home that day after she was “cut,” no one talked about it. It was a taboo topic not to be discussed openly in her home, she says. Only one of their maids approached Fatema and affectionately laughed. Fatema was confused and annoyed when the maid told her she had become a woman now.

When she was 17 years old, Fatema was on Google conducting research for a high school class paper when she first discovered the term FGM. Once she began reading, she gasped. The realization that Fatema had been a victim hit so hard that she immediately ran to her mother and demanded an explanation.

She told me if they didn’t do it, I would’ve gotten sexual urges and that was haram (forbidden), she says

Fatema’s still angry with her mother even though she loves her and understands that in her mother’s mind, she was making the best choice.

But Fatema’s generation of Bohra women are much more educated and are quietly fighting against FGM in various ways. Some are speaking out about their experiences in the media, others are reporting the clandestine clinics and houses where it takes place. Older daughters stop their mothers from putting their younger sisters through it. Even some Bohra fathers are beginning to step in.

Five years ago, Fatema received a call in Pakistan from her cousin’s husband in Chicago. He wanted to know how painful the process would be for his daughter. Fatema told him and her cousin that FGM was illegal in the US and painful, that they shouldn’t put their daughter through the humiliation. “I was fighting about it with everyone in the family, but no was listening. They knew it wasn’t legal, but they did it to their daughter in Chicago,” Fatema says, defeated.

Now Fatema has a niece, her brother’s daughter, who will soon become of age to become another victim in Pakistan. But Fatema and her brother’s wife have a secret plan to save the little girl, one she’s not comfortable revealing publicly. Fatema hopes the doctors in Michigan will be found guilty of performing FGM, and that their guilty verdict will be a lesson for her community to stop abusing its girls. “This is an awful tradition. We have to shift our beliefs. It has to end,” Fatema says.